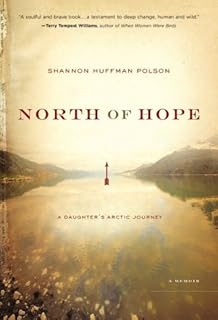

I rarely read memoirs, and requested this book by mistake because I thought it was fiction. What else could it be when a couple is mauled and killed by a grizzly bear? That just doesn’t happen in real life. To my chagrin, the book that arrived was a memoir, North of Hope by Shannon Huffman Polson, the daughter of one of the people killed by the grizzly. I opened the pages, not quite knowing what to expect, and was greeted by two old friends: Ralph Waldo Emerson and Christian Wiman. “This has promise,” I told myself and waded in, identifying almost immediately with Shannon’s need to know answers—under the premise that sufficient knowledge will turn back the clock. But as she discovered, there really are no answers that satisfy.

I thought it was fiction. What else could it be when a couple is mauled and killed by a grizzly bear? That just doesn’t happen in real life. To my chagrin, the book that arrived was a memoir, North of Hope by Shannon Huffman Polson, the daughter of one of the people killed by the grizzly. I opened the pages, not quite knowing what to expect, and was greeted by two old friends: Ralph Waldo Emerson and Christian Wiman. “This has promise,” I told myself and waded in, identifying almost immediately with Shannon’s need to know answers—under the premise that sufficient knowledge will turn back the clock. But as she discovered, there really are no answers that satisfy.

I followed Shannon through the funeral, cleaning out the house, and resuming her own life, hoping for a point of connection; I recently buried my mother. But the numbness of death continued through the reading of this well-crafted memoir, and despite its heavy subject, I could not get past the craft to probe the depths. Here’s a look at the funeral:

A few days later, one of Dad’s colleagues shook his head and looked into the distance. “It’s hard to believe,” he said. “I saw him every day of the work week and some weekends for twenty-five year. I can’t believe he’s gone.” I felt a twinge of jealousy. He’d spent more time with my dad than I had. . .

The cemetery in Healy sits on a hill framed by mountains of the Alaska Range. Dad and Kathy’s friend Shorty, who lived nearby, said that he walked his dogs there every day. It was the place with the best view of the northern lights when they danced in fall and winter night skies. The tundra was decorated with early fireweed and lupine, a fence of spruce trees. Shorty had dug a perfectly square grave facing east to hold both coffins and hauled away most of the fill. . . Dad’s army friend George and his wife, Joanne, stood off to the side next to a lone pine tree, as though unable to step any closer to that hole, as though standing next to the tree might protect them somehow.

Father Jack performed the service for our small group standing on the Alaskan tundra. The mountains stood witness, watching familiar scenes of death and grief that played like shadows on their slopes each day.

I stood at the corner of the chasm closest to Dad’s coffin. My breath came shallowly, a susurrus leaking oxygen to thick reluctant blood. I knelt. I kissed the hard, cold surface of the coffin. The week caught up with me like a rifle shot. I touched the coffin with faltering fingers. Again. And again. The dark, gaping hole. The cold boxes. My legs gave way. Pages 113-114.

Shannon, an avid adventurer, decides to retrace her father’s path and raft along the same wild Alaskan river.

It was a sacred journey. A pilgrimage. But surely it was not only about a river. The river flowed by, running, always running. I wanted it to stop. I wanted it to flow in reverse. I wanted there to be a dam in the river somewhere far back in the mountains, a lake to catch the water and keep it safe for swimming, for drinking, for watching sunlight dancing on the surface of still waters. But the water flowed mercilessly north. There was healing in the tyranny, and tyranny in the healing. North of Hope, p. 124-125.

On her journey she begins to realize something about herself and some things about life.

“This, it now seems to me, is a difference between people of the land, and people on the land, between humility and hubris. It is why a part of our Western culture looks with envy at indigenous people’s beliefs: they come from a deeper wisdom of themselves and their world than we can hope to reclaim. We envy this, while ignoring the potential of this wisdom in the name of supposed progress, even as such progress continues to erode that wisdom or the possibility of our ever recovering it.” p. 169.

I would not spend too much time pondering these words. It is a mistake to believe that indigenous people (whoever they might be) have cornered the market on wisdom. The Bible speaks often about wisdom because God is the Father of Wisdom. We can stop worrying about losing the wisdom of indigenous people when God’s wisdom is available to any who seek Him.

Shannon did come to realize the limitations of her trip, indeed the limitations of life. “This trip won’t make it okay. It’s never going to be okay. . . . It’s not supposed to be okay. “ p. 178. She realizes this on the river and when she visits her dying grandmother. “I understood why it is said that hearts break. I’d understood for a while now. Underground rivers of sadness scald like fire. And so I felt that ripping and burning of a soul and a heart, breaking in relief at talking to her, breaking in seeing her face and holding her hand, breaking as I felt Dad and Kathy’s absence and knowing they would want to be there too, breaking because I was losing her and I didn’t know how much more loss I could bear.” p. 185

This memoir moved in and out of Mozart’s Requiem and gave me glimpses into the life of grizzly bears and the untamed beauty of the Alaskan wilderness. It was eminently readable. I had hoped that it would give me insight into grief, but it didn’t, perhaps because the author, herself, has no insight to share. This memoir left me as cold as the frigid water of that Alaskan river, and although the author continually tossed me crumbs she was unable to satiate me. But maybe that’s her point. There are no satisfactory answers to life’s most devastating losses.

I received this book free through a book review program. I was not required to write a positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. I am disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.

No comments:

Post a Comment